Now, with the inauguration of the Tamar reservoir, we are finally dealing with real possibilities.

With that in mind, David Wurmser's article is worth reading.

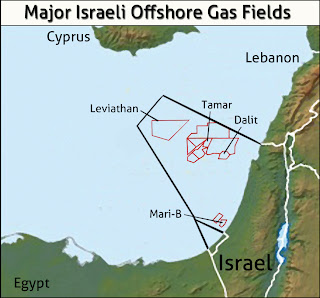

The Geopolitics of Israel's Offshore Gas Reserves

David Wurmser- The flow of natural gas from Israel's Tamar reservoir in the Mediterranean to the Ashdod reception facility was inaugurated on March 30, 2013, ushering in a new era in Israel's energy sector. Israel will not only become independent in being able to supply its own energy needs, but it is likely to become an energy exporter as its maritime gas fields are further developed.

- On January 17, 2009, Israel's economy and even its strategic stature changed when a team led by the Texan firm Noble Energy discovered gas in the Tamar field in the eastern Mediterranean, which is estimated to contain 9.7 trillion cubic feet (TCF) of natural gas. The Tamar well-heads which contain methane gas are rated at a high level of purity, with an energy value of production per well-head over four-fold higher than Saudi oil well-heads. Two years later, the same team drilling a few dozen kilometers further west discovered a monstrous gas field, appropriately called Leviathan, which is now estimated to contain 18 TCF and could begin supplying gas in 2016.

- Tamar was only the beginning. The amount of gas subsequently discovered offshore now dwarfs any feasible, projected Israeli demand for at least half a century. The Tamar field alone represents two decades of consumption. As such, Israel will become a net exporter of gas. The Israeli gas discoveries in the eastern Mediterranean are only part of new gas fields in what is called the Levant Basin, which includes the maritime areas of Israel, Cyprus, Lebanon, and even parts of Syria's waters. The Levant Basin could hold 125 TCF - about one-third of Russia's gas reserves.

- The most likely short-term destination for Israel's natural gas is Jordan. Connecting Israel's emerging gas grid to Jordan is a relatively inexpensive and simple endeavor. Yet Israel will almost certainly have much larger amounts to export.

- Given its geographic proximity, Europe would seem to be the natural export market for Israeli gas. Moreover, Europe is facing a major gas supply crisis because of the spread of instability in Algeria and the rest of North Africa. Yet Asia may emerge as Israel's preferred export destination. The Australian firm, Woodside, which acquired about a third of the rights to the Leviathan field, is oriented toward marketing gas in Asia, and envisions building a liquefaction plant to service that trade.

- Israel's recent experience with Egypt, where half of its natural gas supply was permanently severed following the collapse of the Mubarak regime, suggests that Israel will view with apprehension any scheme to anchor its critical infrastructure in countries beyond its own borders, such as Jordan, Cyprus, or Turkey. Thus, it is likely that ultimately the gas will be liquefied on Israeli territory and exported directly via sea to the consuming market.

- Israeli officials view a cross-Israel natural gas pipeline connecting the Mediterranean and Red Seas as an alternative to the Suez Canal. But an export structure operating directly from Eilat to markets in Asia would face a rising strategic problem: Iran's increasing naval presence in the Red Sea. This will require Israel to establish and expand a Red Sea fleet as well as a significant expansion in the size and capability of its Mediterranean fleet.

Wurmser cautions against jumping to conclusions.

He writes, in part:

Attempts to employ these resources for the sake of advancing peace between Israel and its Muslim neighbors will be the greatest temptation at the policy level. Yet the historical record suggests that increasing co-dependency between Israel and its neighbors and using development efforts to anchor rapprochement among populations are quixotic cul-de-sacs. Such efforts in the past only increased Islamic resentment against Israel and played into their ideologues’ anti-Semitic imagery of Jewish control of their economies. Furthermore, they have left Israel more strategically vulnerable. While some in Israel hope that anchoring Israel’s export system to Turkey and becoming an answer to Turkey’s energy gap will help reverse the strategic foundering of the bilateral relationship, Israel’s experience with Egypt and the Palestinians suggests that such hopes, while well-intended, will meet with great disappointment.Read the whole thing.

David Wurmser, Ph.D., is founder and executive member of the Delphi Global Analysis Group, LLC in Washington. He has served as a consultant to Noble Energy. Earlier, he served as senior advisor on Proliferation and the Middle East to former U.S. Vice President Dick Cheney, as senior advisor to John R. Bolton at the State Department, and as a research fellow on the Middle East at the American Enterprise Institute.

-----

If you found this post interesting or informative, please  it below. Thanks!

it below. Thanks!

it below. Thanks!

it below. Thanks!

1 comment:

Step one is stop buying gas and oil from the Arabs. Step two is stop worrying about gas and oil and diesel fuel transfers to the 'Palestinians'. Just announce a long term plan to do away with all of that and they are on their own.

Post a Comment